This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

At an open shed along the coast of Bortianor in Accra, one can hear the chatter of market women who hang around the landing beach most mornings in hope of buying fish to trade as fishers pull their nets miles away to the shore.

“Sometimes, it takes as long as four hours to bring our nets ashore,” artisanal fisherman George Kowukumeh said. “And over the years, we have witnessed a drastic reduction in our catch.”

According to industry experts, there are currently about 150 fishing canoes operating at the Bortianor landing beach.

In Ghana, the artisanal fishing sector directly employs over 200,000 fishers, delivering 80 percent of total fish supply locally and providing livelihood to over 2 million people including thousands of market women in the value chain.

When it comes to fish, Ghanaian women have traditionally been confined to processing and retailing. The role of women is significant because they add value to fresh fish through processing while distributing and preserving fish to ensure its availability long after the peak season and allowing it to reach consumers far from the landing beach.

However, the near collapse of the pelagic fish stock, which is the main target for artisanal fishers has left fishers and women in the value chain vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

A two-month investigation by Gideon Sarpong based on interviews with dozens of fishery experts, researchers, fishers, and women in the value chain has shown declining income levels for thousands of fishing households partly blamed on climate change and the rise in ocean temperature. A non-existent government intervention program to support fishing communities, particularly women who are very vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change has left them to their fate.

Climate change impact on fishers and fishmongers

It is over three hours since the fishers began pulling their nets at the Bortianor landing beach. There is obvious anxiety among the market women and fishmongers gathered at the shore who buy their fish directly from the fishers.

Agnes Lamptey, a fishmonger for over 30 years explains the reason for the anxiety: “when there is no catch, we do not get any fish to process for selling. We can’t even provide for our children. My children are in high school and are forced to stay at home when there is a meagre catch.”

Moments after the conversation with Agnes, the fishers manage to bring their catch to the shore. “The catch today is disappointing and full of garbage,” local fisher, George Kowukumeh said. “Several hours of tough work has produced less than 500 cedis ($62) worth of fish for the 9-member crew, what do we do with this?”

In 2019, the Sustainable Fisheries Management research revealed that despite increasing fishing effort by the artisanal fishing fleet in Ghana’s waters, small pelagic fish catch has fallen by over 85 percent, from the peak in reported landings of 138,955 metric tonnes recorded in 1996. The researchers blamed climate change and other man-made activities such as illegal fishing as a major cause for the decline in pelagic fish stock in the country’s waters.

Dr. Opoku Pabi, lecturer and senior research fellow at the Institute for Environmental and Sanitation Studies, University of Ghana explained that, “fish catch is strongly related to surface water and atmospheric temperatures; generally, the lower the temperatures, the higher the fish catch.”

“This does vary somewhat across species, however: the catch for Pelagic (round sardinella) peaks when the sea water temperature is at its lowest” he added.

Data from a research paper he co-authored showed that Ghana has experienced a, “steady rise in atmospheric and seawater temperatures since the 1960s, with the latter increasing by an average of 0.011degree Celsius yearly.”

The paper also noted that the: “end of the rainy season” which traditionally signals the start of the main fishing season has become very “unpredictable due to variability in rainfall distribution patterns, exacerbating poverty and indebtedness among artisanal fishers and women in the value chain.”

Traditionally, women in the fishing communities across Ghana – particularly, the queen fishmongers – have owned boats and financed trips, guaranteeing them a portion of the catch.

But this traditional system is giving way as profits fall. Fishmonger, Agnes Lamptey whose husband is also a fisherman counts her loses after investing in the day’s fishing trip.

She explained: “the fuel prices are expensive. I contributed 100 cedis ($12) to the day’s fishing trip and they returned with basically nothing. So can you imagine, I lose about 3000 cedis ($370) in a month if there’s no daily catch. We are really suffering especially, we the women. We need money to take care of our children and keep our business going.”

Steve Trent, chief executive of Environmental Justice Foundation, an NGO that monitors economic and environmental abuses has warned that any further decline in Ghana’s fish stock, particularly pelagic species would be, “catastrophic and have huge socio-economic costs.”

A 2021 study which focused on the effects of decline in fish landings on the livelihoods of coastal communities showed that decline in fish landings has “translated into low-income levels” for households that have directly depended on fishing over the years.

According to the study, 53 percent of fishing households maintained that they had seen a reduction in their incomes over the last five years.

Closed fishing season – a painful solution?

In response to the dwindling fish stock in Ghana’s waters, the Fisheries Ministry in April, 2022 announced a one-month closed fishing season for artisanal fishers and semi-industrial vessels which began on July 1st. The minister, Mrs. Mavis Hawa Koomson in a statement argued that the “closed season was agreed on based on scientific evidence and stakeholder consensus to reduce the excessive pressure and over-exploitation of stocks in the marine sub-sector which will help replenish the fish stocks.”

Despite the consensus among various stakeholders on the need to protect spawners from capture during the breeding season, fishers and women in the value chain in several fishing communities including at Jamestown, Elmina, Tema and Bortianor have fiercely rejected this directive.

Jacob Tetteh, spokesperson for fishers at the Bortianor landing beach insisted that the closed season must be “scrapped” despite admitting to a drastic reduction in fish catch over the years.

“The fisherfolks work is not like government work, what they get is what they spend in the house every day. So how will they survive during this period” he argued.

“What will happen to all the women and their kids who depend on the ocean for their livelihood? A loss of revenue for a single day affects the entire community.”

The fisheries minister did not respond to requests for comment.

The world has already warmed more than 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) since the preindustrial era, and last year the oceans contained more heat energy than at any point since record-keeping began six decades ago.

According to a study published in the Journal of Science last April, if humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions continue and the ocean’s temperature continues to increase, roughly a “third of all marine animals could vanish within 300 years.”

Way forward

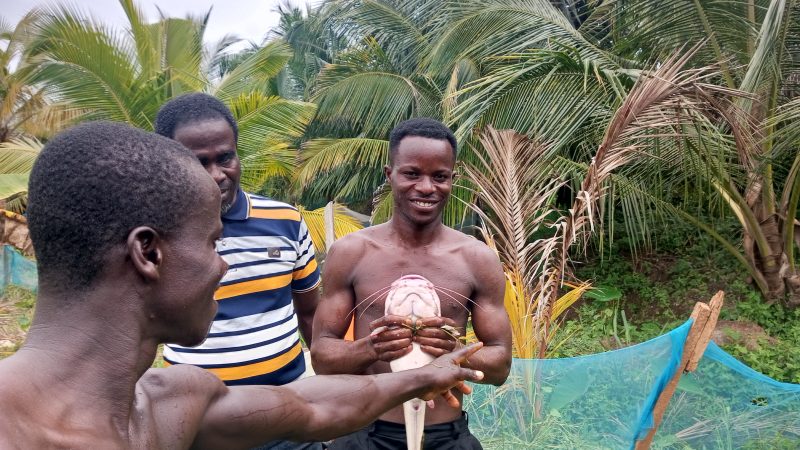

To reduce the vulnerability of climate change impact on Ghana’s fishery sector, particularly women in the value chain, Daniel Doku Nii Nortey, deputy director of coastal resources NGO Hen Mpoano, has recommended retraining and a skills development program for fishers and women processors.

The state must invest in “alternative livelihood training programs such as soap making, hairdressing, tailoring etc. in coastal communities,” Daniel said. “These will help families diversify their source of livelihood.”

For the many fishers and women in coastal communities across Ghana, the struggle for survival stares them in the face each morning.

“It is a hopeless situation,” said fishmonger Janet Mensah who inherited the trade from her mother over 20 years ago.

“I do not know what the future holds for me and my children in this profession, it all doesn’t make sense to me again. We need help.”